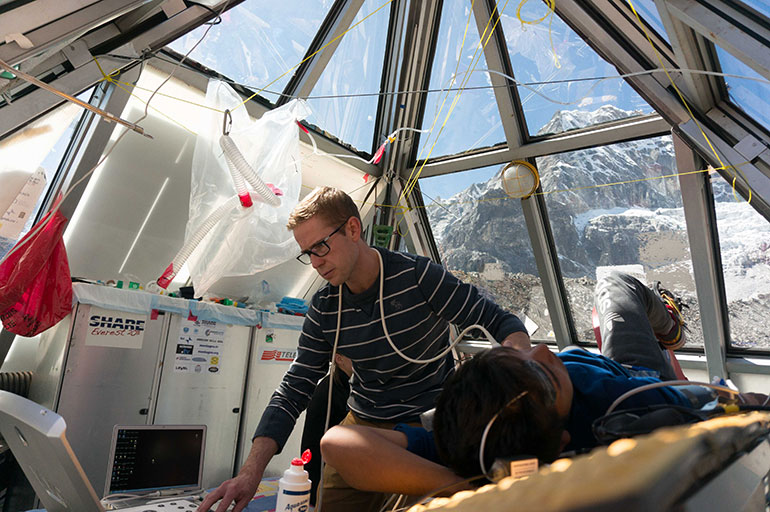

A picture captured by Prof. Ainslie’s research team during their high-altitude research expedition to White Mountain, California, in 2015. Photo credit: Matt Reiger

How do high-altitude residents and deep-water divers thrive where others cannot?

UBC Professor Phil Ainslie’s research has taken him from extreme mountain peaks, to the wild edges of the globe and to the cold depths of the ocean. His quest is to understand why and how some thrive in conditions that make the average person extremely ill.

A Canada Research Chair in Cerebrovascular Physiology in Health and Disease, Ainslie has spent his career studying hypoxia—reductions in oxygen tension, content (hemoglobin) or both. When the brain and other organs are deprived of oxygen or blood, a person may become ill, suffer permanent damage or even die.

Understanding the physiology and genetics of human hypoxia tolerance has important medical implications, says Ainslie, a professor in the School of Health and Exercise Sciences.

“So far this phenomenon has been poorly investigated in high-altitude human populations such as Nepal’s famous Sherpa, and to an even lesser extent in unique populations of free-hold divers,” he explains. “Some of the free divers we’ve studied can hold their breath a remarkable 25 minutes. And they willingly put themselves in the most severe state of hypoxia for either spear-fishing or breath-holding competitions.”

While working with some of the world’s best free divers based in the Mediterranean, Ainslie’s team explored how their lungs, hearts and brains respond to extreme reductions in oxygen tension, and how they were able to train their bodies to withstand such pressures.

In a study published this spring in Experimental Physiology, his team outlined the relevant physical characteristics and mechanisms that make extreme breath-holds possible for people participating in competitive apnoea. Ainslie states a better understanding of these factors during seemingly insurmountable voluntary breath-hold situations is relevant for many reasons including a safety and medical point of view.

“This kind of research is not only important to the ‘elite’ breath-hold divers, but also for people who live with progressive lung issues from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD--which includes emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and several strains of asthma), heart failure or people who go into intensive care,” Ainslie says. “This research is important for any groups who have changes in blood flow that affect the delivery of oxygen to various organs as these affect their pathology, their quality of life and their doctor’s ability to treat them.”

The eventual goal of Ainslie’s globetrotting is to understand how some populations can adapt (or maladapt) to their natural habitat, with the aim of coming up with new methods for prevention and treatment of such illnesses.

Conducting research at different altitudes, and on people who have lived at high altitude their entire lives, has led Ainslie and his team to more than 100 research publications related to medicine and physiology. Over the past 15 years, Ainslie and his international team of researchers have travelled to the Himalayas numerous times to study the high altitude-adapted Sherpa population. Research has also taken place at White Mountain, California, and Croatia with free-hold divers. The team is now about to embark on a trip to Peru.

UBC Okanagan PhD candidate Mike Tymko, is organizing the large-scale Peru expedition. While there, the team of more than 45 co-investigators will spend a month at Cerro de Pasco, a mining town at 4,330 metres. Along with several high-altitude studies that will be conducted on native low-landers, they will also work with a group of Andeans who have developed a genetic mutation and live at high altitude with a condition called chronic mountain sickness.

“There are some high-lander Andean natives who have maladapted to their environment and developed an advanced form of altitude illness where their blood becomes extremely thick,” says Tymko, the co-leader of the pending expedition. “They work at local silver mines while suffering from chronic mountain sickness. This leads to them having an excess of red blood cells in their body—it’s like their heart is pushing sludge through their blood vessels—they work through their illness in order to financially support their families.”

One of the main goals of the trip to Peru is to learn more about this maladaptation and explore potential treatment avenues that might keep the Andeans at work in a healthier manner.

“The neat thing about our model is everyone who is coming is a study subject,” adds Tymko. “Last month, we had 35 researchers—who are all coming to Peru—in our UBC Okanagan laboratory every day for sea-level testing. In June, we are all meeting in Peru so we can repeat these same experiments at high altitude. In addition, we will be conducting a series of these experiments on the local Andean high-altitude natives.”

They will conduct 15 research projects involving several different stressors, including pharmacological and exercise interventions.

The international research team represents universities in Canada, United States, New Zealand, Austria, United Kingdom and Peru, and includes world experts in high-altitude physiology and medicine. Cardiff University’s Mike Stembridge—who has participated on several research trips with Ainslie and Tymkoin Croatia and White Mountain in California, and twice in Nepal—is also heading to Peru with the team.

This week, he published a study from research conducted at high altitude at White Mountain. The study, published in the Journal of Physiology, unearthed why the human heart does not function as well at high altitude. The researchers determined a combination of the decrease in the volume of blood circulating around the body, and an increase in blood pressure in the lungs, limit the volume of blood the heart can eject. Stembridge says it’s important to note that neither of these factors affect a person’s ability to perform maximal exercise.

After Peru, the team will begin to plan their next expedition—this time to Ethiopia to study a group of highlanders who live at about 3,600 metres. Again, they want to examine the physiological and genetic make-up of people who continue to thrive at an altitude that makes most people ill.

“What’s really important when we talk about the Nepalese, Peruvian and Ethiopian high-altitude natives is that we probably only have about 50 years left to study them. Their genetics will soon be lost,” Tymko says. “The people who have been living at high altitude for centuries are coming down, mostly looking for the jobs that offer a higher income at low altitude.”

Forever curious, Ainslie admits his search for answers and treatment options will continue to take him to the edges of the Earth.

“After Peru and Ethiopia, our goal is to focus on the indigenous Bajau people, the ‘Sea Nomads’ of Southeast Asia,” he says. “They live a subsistence lifestyle based on breath-hold diving and they are renowned for their extraordinary breath-holding abilities.”

Mike Stembridge conducting tests at Everest’s Pyramid Lab.

Picture of a Croatian free-diver

About UBC's Okanagan campus

UBC’s Okanagan campus is an innovative hub for research and learning in the heart of British Columbia’s stunning Okanagan Valley. Ranked among the top 20 public universities in the world, UBC is home to bold thinking and discoveries that make a difference. Established in 2005, the Okanagan campus combines a globally recognized UBC education with a tight-knit and entrepreneurial community that welcomes students and faculty from around the world. For more visit ok.ubc.ca.

Stanley Cup Playoff etiquette

Stanley Cup Playoff etiquette A sea can is not a shed

A sea can is not a shed Sentencing finally set

Sentencing finally set Senators reject field trip

Senators reject field trip 'City within a city'

'City within a city' Searching landfill for woman

Searching landfill for woman Israeli strike played down

Israeli strike played down Full Trump jury seated

Full Trump jury seated World's largest election

World's largest election  Lululemon cuts 100 jobs

Lululemon cuts 100 jobs Bitcoin's 'halving' arrives

Bitcoin's 'halving' arrives Lawsuit over missing nuts

Lawsuit over missing nuts Warriors ready for Round 2

Warriors ready for Round 2 Kalamalka Bowl cancelled

Kalamalka Bowl cancelled Rockets live to fight on

Rockets live to fight on Pulp Fiction turns 30

Pulp Fiction turns 30 Chris Pratt injured in movie

Chris Pratt injured in movie My name is not Elaine

My name is not Elaine