Women and people of colour are dramatically underrepresented in STEM fields. The fix may begin in kindergarten.

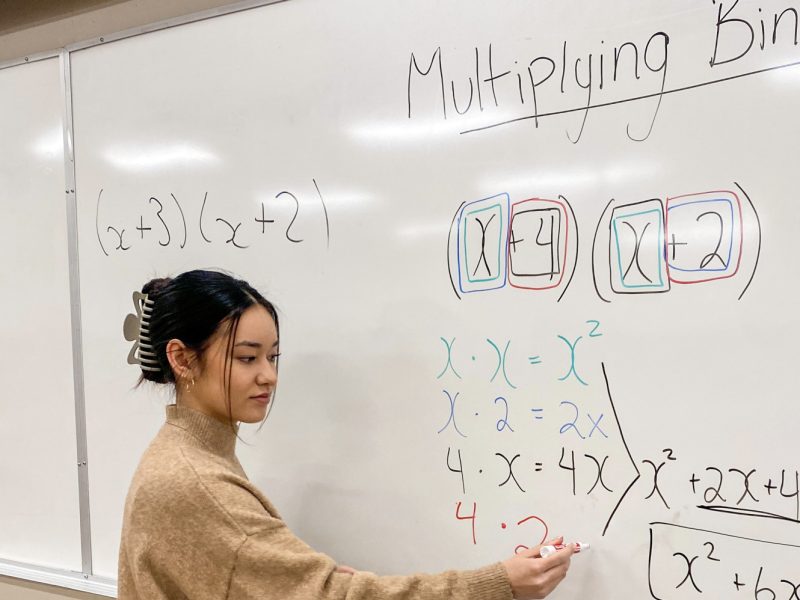

In a recent lesson with a Grade 11 chemistry class, practicum student Ayame Byrne discussed the Bohr diagram: a description of the structure of atoms, proposed by physicist Niels Bohr in 1913.

Bohr, like many of the acclaimed scientists who Byrne learned about when she was in secondary school, was a white man. As a university student studying biology and ecology, most of her professors were white men. Now, as a Bachelor of Education (Secondary) STEM student at TRU, Byrne considers how she can make her lesson plan relevant to the students in her class.

“Many of the major scientific discoveries that I was taught are mostly attributed to white men,” Byrne says. “I make an effort to bring more women in the classroom who have made scientific discoveries. In class we’ve also talked about how important it is to do different activities, games and labs to explore their learning, rather than traditional lessons of lectures and tests.”

Inequity by the numbers

Ten years ago, the United Nations declared February 10 the International Day of Women and Girls in Science to raise awareness of the lack of diversity in STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math). Its most recent report found that in Canada, women account for 19 per cent of engineering grads. At Apple and Google, fewer than one-quarter of technical roles are held by women. And in higher education and research, women researchers tend to have shorter careers, and only 12 per cent of members of national science academies are women.

Much of the conversation around inequity in STEM focuses on numbers. While the numbers show a troubling pattern, Dr. Mahtab Nazemi, who teaches future STEM secondary teachers in TRU’s Bachelor of Education program, proposes that people’s experience in the classroom — starting as early as kindergarten — is key to addressing the lack of diversity.

Dr. Mahtab Nazemi

“On the one hand we all recognize that representation matters, but it isn’t the whole story,” Nazemi says. “You can’t look at a classroom of girls or black and brown kids and decide that it must be an equitable space simply because they are surviving there. A lot of women have done well in mathematics, but you don’t know how they have been supported: are they having to perform whiteness or being a tomboy to succeed, or are they able to be themselves? You can’t depend on people’s resilience.”

In a recent study, Racialized Narratives of Female Students of Color: Learning Mathematics in a Neoliberal Context, Nazemi looked at the experiences of six girl students of colour in an Advanced Placement Statistics class in a Seattle area high school.

In many ways, the classroom looked like an equity success. Nazemi describes the teacher as race aware, and she had tailored her lesson plans to allow time for the students to explore their own projects where they used statistics to explore issues relevant to their daily lives: how the availability of grocery stores versus convenience stores correlate to levels of diabetes and dental issues; how criminal charges for marijuana possession vary by race and class.

Consider cultural context

“Students often say, ‘Why do I have to learn math?’ So if you can build curriculum around students’ lives, it makes a world of difference. Just as language learning doesn’t happen without context, math learning needs content and context,” Nazemi says.

Still, Nazemi says her study confirms that math is a great place to look at equity; while we tend to assume that mathematics and numbers are the same in every language, in the mathematics classroom, race and other social locations affect how teachers and students relate to each other, how teachers teach and how students learn.

She emphasizes the importance of self-reflection for teachers, and shares a story with each class of new TRU students about her friend, who grew up in a small city in northern BC. She recalls shared meals at kindergarten where the teacher would ask each student to take turns telling the group what they had for breakfast.

“My friend would say ‘rice.’ And the teacher would correct her: ‘No, what do you have for breakfast?’ So she learned to say ‘eggs’ or ‘oatmeal.’ As a five-year-old, she learned that her truth was not correct,” Nazemi says. “We learn to leave parts of ourselves at home, and that goes for all kinds of things: gender, race, culture, food.”

Byrne graduates this June, and hopes to teach in her own STEM class. She attributes part of her decision to become a science teacher to her own experience. She completed her Bachelor of Science degree in the state of Maryland, and at one institution, she had women professors in classes she hadn’t before: organic chemistry, calculus 2 and Principles of Ecology and Evolution.

“Having that representation was important to me, and it influenced my own direction and career choice,” she says. “And being in the STEM program and seeing the instructors who are teaching future teachers has been a really uplifting experience. We have a lot of conversations about inclusivity and everything we’ve learned is geared toward student-centred learning. I think we are moving in a positive direction with more women entering the field and empowering other young women to feel confident in STEM.”

Online harms bill on hold

Online harms bill on hold BC boosts milk production

BC boosts milk production Baby lives after stroller hit

Baby lives after stroller hit Plastic treaty talks underway

Plastic treaty talks underway UN workers charged

UN workers charged  Trudeau in Saskatoon

Trudeau in Saskatoon  $620 million for Ukraine

$620 million for Ukraine  5 die crossing channel

5 die crossing channel Jury finds railway at fault

Jury finds railway at fault  PepsiCo beats Q1 forecasts

PepsiCo beats Q1 forecasts Equifax testing rental data

Equifax testing rental data  Tourism operators struggle

Tourism operators struggle  Leafs even series

Leafs even series Cristall gets pro look

Cristall gets pro look Warriors even series in OT

Warriors even series in OT Hozier surprised by #1

Hozier surprised by #1 Trainor to replace Perry?

Trainor to replace Perry? Swift breaks Spotify record

Swift breaks Spotify record